Editor’s Note: This is a guest post from MovNat founder Erwan Le Corre.

“A pattern that had been familiar throughout history is that after a war is fought and won, the tendency is for society to relax, enjoy life, and exercise less. … It appears that as societies become too enamored with wealth, prosperity and self-entertainment, fitness levels drop. In addition, as technology has advanced with man, the levels of physical fitness have decreased.” –Lance C. Dalleck and Len Kravitz

In the late 19th century, Dudley Allen Sargent – virtually the founder of physical education in America – warned that without solid physical education programs, people would become fat, deformed, and clumsy. Sound familiar?

Fitness has become accessory to the life of the modern man. It is up to each of us to exercise or not. Most people don’t, and being out of shape has become both ubiquitous and commonly accepted. It has become okay to be a physically soft, inept grown-up. Superficial, cosmetic improvements in body shape remains the primary motivation to the few who exercise, and globo-gyms are filled with “mirror-athletes” — people obsessed with their own reflection.

But looking fit and being fit are not necessarily the same. Being fit is being capable of performing physically in the real world with effectiveness and efficiency, and especially when the situation and the environment are challenging.

Enter MovNat. MovNat (natural movement) is a physical education system and fitness method dedicated entirely to developing such capabilities. A “movnatter” believes that there is more to building the body than just building muscles, and that there is more to building a man than just building his body. Traditional physical training once combined physical and mental strengthening into one integrated whole and emphasized the vital necessity of preparing for the practical demands of life. Today, MovNat perpetuates this mentality and philosophy. Natural human movement is not an option. It has always been, still is, and will always be a biological necessity. In a world crowded with an increasing number of disempowered men, the timeless endeavor of real-world preparedness is once again becoming a fundamental component of the art of manliness.

The History of Physical Training

If you think that fitness started with aerobics and body-building, Jane Fonda and Arnold Schwarzenegger, think again. The history of physical training and education is made of a long line of ancient peoples, tracing back to the Assyrians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Persians, and later on, the Greeks and Romans. Preparedness for battle was the principal purpose behind physical training. Following the Dark Ages of the medieval times, the Renaissance era prompted a renewed interest in the body, health, and physical education, especially in the work ofMercurialis.

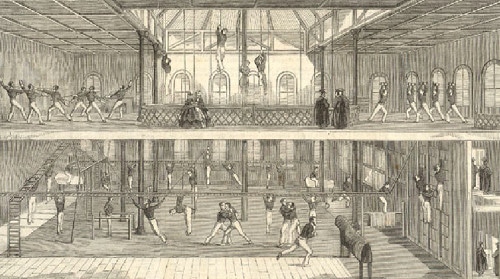

Starting with the Industrial Revolution and up until the early 20th century, a series of important pioneers of physical education — Johann Bernard Basedow, Guth Muths, Friedrich Jahn, Gustavus Hamilton, Archibald MacLaren, Francisco Amoros, Georges Hebert – built the foundation of physical training: gymnastics and calisthenics. And not the modern versions which focus on acrobatic moves or strength conditioning.

Instead, early gymnastics and calisthenics prioritized practical skills, with effective applications to the real world: running, jumping, balancing, crawling, climbing, lifting and carrying, throwing and catching, swimming, boxing, wrestling, horse riding, stick fighting, and fencing. Below, you’ll find three examples of men who sought to retain natural body movements as a means of physical fitness:

- In 1815 in Germany, Friedrich Jahn, the “Father of Gymnastics” developed exercise clubs called the Turnenvereins, which were outdoor exercise facilities with apparatuses designed for running, jumping, balancing, climbing, vaulting, etc.

- In France in 1819, Francisco Amoros, a military man originally from Spain, organized the Normal Gymnastic Civil and Military School. He developed a system of gymnastics that also included work on apparatuses and calisthenics. In 1830 he published a book titled A Guide to Physical, Gymnastic, and Moral Education. His system became known as the “natural-applied” system.

- In 1905, Georges Hebert created a similar system called “Physical, Virile and Moral Education by the Natural Method.” Similar to his predecessors, the whole method relied on the practice of natural and utility exercises such as walking, running, jumping, balancing, crawling, climbing, carrying, etc. He advocated a “reasoned return to nature” to be beneficial to the “weak and degenerated” civilized man.

The main point is to realize that what we know as fitness or working out is quite a new thing. It’s become a large industry offering a confusing plethora of varied and diverging concepts and programs that everyone is free to pick from and is pervaded to the bone by marketing gimmicks. For many centuries, men have been using simple, no-nonsense methods. They have dedicated themselves to developing their body and mind by honing their natural movement skills. They have been keen to prepare themselves for the practical demands of the real world, by moving and performing physically in useful ways. It is a radically simple, yet highly effective approach.

Principles of MovNat Training

While the MovNat methodology incorporates concepts of bio-mechanics, kinesiology, and exercise science, it is also the modern version of these ancient physical training methods. Discover some of our essential guiding principles below.

Prioritize Practical Movement Skills

Natural human movement comprises locomotive skills such as walking, running, balancing, jumping, crawling, climbing, or swimming; manipulative skills such as lifting, carrying, throwing, and catching; and combative skills such as striking and grappling. In today’s comfortable world we are losing sight of the practicality of these skills, yet their value cannot be ignored whenever a life-threatening situation arises. You might have to run for your life, or climb, swim, fight, lift, etc. These abilities can save not only your own life, but that of strangers and loved ones as well. George Hebert said, “Be strong to be useful.” Do you want to be strong and useful? Then prioritize practical ways to move.

Get Real and Aim for Effectiveness

Our take on effectiveness is not limited to counting sets and reps. Effectiveness is the ability to get the job done within a variety of contexts, including a great range of environments and situations. Maybe you can do pull-ups, but have you ever tried climbing on top of a thick, rounded and elevated horizontal bar (or tree branch) from a deadhang? If you’ve never checked on your actual ability to be effective at something practical like this, then how can you possibly know if you can? Do you know the different ways it can be done? Don’t just assume your capability. You want to train your effectiveness in varied environments and situations and regularly put it to the test.

Develop Efficient Movement Skills

Managing effectiveness is great, but physical competency for practical performance requires more than that. Let’s say you tried, and did manage to climb on top of the bar or tree branch. How many attempts did it take? How much time did it take? Were you hesitant, maybe afraid? How much energy did you expend, and how safe was it? Could you do it several times in a row without losing efficiency? Effectiveness is the ability to perform a task successfully regardless of the cost; efficiency is the ability to perform a task successfully at a high level at the lowest energy cost possible, and with the greatest level of safety possible. Anyone can run, jump, climb, etc., to some degree, but not everyone can do it skillfully. By emphasizing efficiency and developing specific physiological adaptations, you can acquire a level of mastery that goes beyond what is purely innate.

Cultivate Adaptability

We’ve mentioned the pull-up, which is a practical movement as well as just an upper body strength conditioning drill. It is actually a discrete component of an upward climbing motion; it requires strength and limited motor control. Now this is the bad news: your effectiveness and efficiency at any given climbing action are absolutely NOT guaranteed by just training pull-ups. This is called the SAID principle: Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands. By only doing pull-ups on the same regular pull-up bar, you become adapted to this specific demand, but notadaptable to other climbing patterns or environments. In short, pulling up is climbing, but climbing is not just pulling up.

Let’s say you can do regular pull-ups (prone grip, chin to bar, no kipping), hanging from a regular pull-up bar. Now find a thicker (say, 4 inches wide), smoother bar, like some of the metal structures used for swings at the playground (like Brett has already shown us!). Can you do as many pull-ups as you normally can do at the gym or at home? It is likely you will do significantly less reps because of a lack of grip strength. Say that as part of your regular workout program you can jump 50 times on a two-foot high plyobox. Today, you have to jump only once…but over a 12-foot-wide and 12-foot-deep gap, with a 3-4 step run-up, and you must land on a narrow surface with barely enough space for both your feet. Could you do it?

Apply the same reasoning to other types of movements and contexts. How much of your fitness training transfers to a variety of practical challenges? How adaptable are you to different environments? No amount of extra strength conditioning will compensate for a lack of specificstrength conditioning or motor control.

Train Mindfully

The mind of today’s man is constantly distracted by various sensory stimuli. While using exercise machinery at the gym, it is likely you will listen to music, watch TV, and think of something else. Your body is in one place and your mind in another, trying to escape the boredom of the fitness chore.

MovNat is different for three reasons. It is based on real movements, not muscle-isolation. Second, the practical nature of what you are doing is obvious: “I’m jumping over this obstacle, I’m climbing on top of this bar.” Finally, the movement is adaptable. If you jump, you may have to accurately land on a restricted surface, in a stable way. Your mind cannot wander, because there is a practical task at hand within an environment that can’t be ignored and that you must adapt to. Both your mind and body have to be in the same place, at the same time. This is mindfulness; pure presence in the moment, where you are, doing what you’re doing. In today’s hectic life, mindfulness has become a rare skill, and a priceless experience.

Awareness, alertness, focus, and responsiveness are all part of the art of mindfulness, and no physical competency is possible without it. Mindful practice is your opportunity to simplify and reconnect the mind to the body, to the environment, and to the moment.

Ensure Progressions and Safety

It is common to see people, after years of neglecting their body, trying to reverse the negative physiological effects of decades of physical abandon by brutalizing their body back to fitness in a matter of weeks. This culture of immediacy and instant gratification deserves a severe backlash.

This is why progressions and programming are an essential part of the MovNat system. You will practice the “side swing traverse” before you practice the “elbow swing-up,” and the “tuck pop-up” before the “muscle-up.” You will train simple balancing walks on a 2×4 board at floor level and maybe someday end up safely walking across a fallen tree above a deep canyon. You will build skills, strength, conditioning, and mental toughness gradually. Practice mindfully, progressively, and safely.

Spend Time in Nature

Modern man, just like his ancient ancestors, needs to regularly spend time in nature if he wants to be optimally healthy. Nature is the original habitat where he was able to emerge as one the most successful species on Earth. Indoor, controlled environments are very useful to get people started moving naturally in a safe and scalable manner. But the revitalizing effect of nature has been repeatedly proven by science. Moving naturally in nature is extremely beneficial to physical and mental health. Try it!

How to Get Started

Re-explore

A simple way to get started with MovNat is to re-explore your potential for natural movement. If you think about the different ways you move each day, you’ll realize they are not very varied and stick to a fairly rigid pattern. Get out and find or create opportunities to move naturally (running, jumping, crawling, balancing, climbing, carrying, etc.).

This approach is simple and effective, but keep in mind the essential difference between natural as done spontaneously but not necessarily effectively, efficiently, or safely, and natural anddone effectively, efficiently, and safely. Without guidance, you may not even be able to feel the difference between good technique and bad form, and take risks you are not prepared for. Knowledge, technique, mindful practice of efficient movement, and the respect of progressions (volume, intensity, and environmental complexity) are the keys for a successful transition from the innate but inefficient, to efficiency and competency.

Learn

Since we’ve used the example of pull-ups vs. practical climbing, as an example of the learning process, how about trying the easiest way to climb on top of a horizontal bar (or large tree branch) from the deadhang position (also known as the “sliding swing-up”). “Easiest” doesn’t mean it is necessarily easy, and it can be quite challenging to the beginner. This simple test might show you that what is spontaneous is not always effective, and what is effective is not always efficient. Use the guidance below to boost both your effectiveness and efficiency!

- Find a horizontal bar or tree branch about 6 to 8 feet above the ground that is strong enough to support your weight and not move. The thickness should ideally be between 2 and 4 inches. Make sure the surface underneath is clear of any obstacle you could stumble or fall on. You may ask a friend to spot you for additional safety.

- Start from the split deadhang (arms apart, hanging like a limp noodle), the body perpendicular to the bar. Secure a firm grip with both hands, hanging still, and keeping both arms fully lengthened.

- Without pushing off the ground with your feet, generate a forward swinging motion by lifting both bent legs up and to the front, then down and to the back.

- When you’ve gained enough momentum, swiftly lift both legs up as you’re swinging forward and pinch the bar between the feet. The foot pinch requires accuracy; look up and focus on making sure you will effectively secure the “foot grip.” If you lack abdominal strength and lifting your feet at bar level is too difficult, you can try assisting by pulling up with your arms.

- From this “sloth” position, pull from the feet and hook one leg over the bar. The leg is strongly supported by placing the hollow at the back of your knee (“popliteal space”) on top of the bar, not the calf.

- Release the inside hand (left hand if your left leg is hooked) and bring the crease of the elbow (“antecubital space”) over the bar, or the forearm directly.

- Pull the outside arm up and place the forearm on top of the bar. From there, slide the armpit of the inside arm forward on support on the bar, then place the other armpit in the same position. At this point, your bodyweight is securely supported by 3 points of support, the back of the knee and both armpits. The opposite leg is relaxed hanging down in the void.

- Pull the free leg all the way up (fully extended or slightly bent) and swiftly swing it down to generate momentum (“bodyweight transfer”). The swift motion of the leg will elevate your center of gravity by lifting your bottom up. Keep the lats and hooked leg tight to maintain a secure position.

- As your body is being elevated, both armpits move up over the bar, arms sliding forward, allowing you to pull from the inside of the upper arms.

- As you start pulling from the arms, immediately lean sideways and forcefully push off the back of the knee of the opposite leg, allowing the body to fully extend in length across the top of the bar.

- End up stable on top of the bar, bodyweight supported by the flank and the inside of the opposite leg. Reposition your body, for instance in a straddle stance.

No comments:

Post a Comment